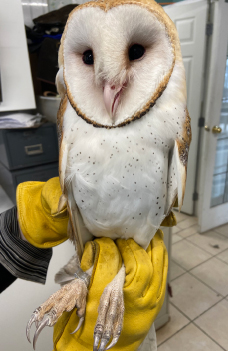

OWLS AT RISK

Human Habits Put Raptors In Danger

By Michael LaChance

Near-perfect depth perception, binocular vision and necks that rotate 270 degrees — yes, we’re talking about owls. From Hedwig to Big Mama, these intriguing birds are full of beauty, mystery, and spot-on predatory instincts. We’d all love to be surrounded by a parliament (fun fact: that’s a group of owls) of them. However, it’s best to leave them to their own devices.

You see, for the best chance of survival, owls need food and nesting trees — but most importantly, they need a habitat free from humans. And, apart from our development ruining their habitats, some of our habits are putting them in grave danger. Here’s a practical guide to what they need, and why you should never, ever keep them as pets.

HUMANS: THE BIGGEST THREAT

Most threats owls face are avoidable, and caused by us! As Rob Hope, Raptor Care Manager at OWL (Orphaned Wildlife) Rehabilitation Society says, “Human disturbances are development-related — nesting trees and habitats are removed for roads and houses.” Paul and Nicola of The Owl Sanctuary expand on the threat we cause, telling us it involves everything from the unassuming fences and outdoor decorations to the more obvious poison and poaching.

They explain that rodent poison remains in the animals bodies, and can kill owls who later feed on these creatures. Low-flying owls are vulnerable to passing cars, and they can be tangled in fencing. Whatever the regulations in different countries, poaching and stealing eggs are also a grave threat. They’re even disturbed by bird-watchers!

Liberty DeGrandpre, from The Owl Research Institute, adds, “Warming temperatures will have an impact, as well. For Snowy Owls, whose breeding populations are declining in our study area of the Arctic, it may already be impacting their critical prey species, the brown lemming. For Great Grays, another northerly owl, we may see them moving further north. Owls inhabit such diverse habitats that climate change affects each species differently. Forest thinning, fire management, grazing, insect outbreaks, are all threats to owls.”

As Rob adds, “Climate change is also affecting owls, especially with more frequent forest fires that are burning hotter and causing more extreme deforestation.”

And don’t forget about new farming practices. Daniel Cone, Assistant Director at the World Bird Sanctuary explains, “These have altered the landscape enough to significantly reduce native wildlife populations. Mono-cropping, heavy fertilizing, and the reduction of fencerow space have made farmland uninhabitable for many native species.”

YOU CAN CHANGE THINGS

If you think there’s nothing you can do to help, think again. As Daniel says, “There are many things that can be done to help owls. Just asking what you can do is a great start!”

Liberty emphasizes leaving owls alone during their nesting time. “Interested observers and photographers can create problems, even causing them to abandon their nests. Getting too close and flushing a female from her nest can lead to sad consequences,” she explains. She also suggests voting for environmentally friendly politicians and supporting conservationists and researchers, financially and otherwise.

Paul and Nicola give us additional tips to help owls survive among us:

• Use traps, not poison for rodents.

• Drive slowly and look out for flying owls, especially at night.

• Make fences more visible and avoid barbed wire or razor wire.

• Keep outdoor decorations or anything that can obstruct flight paths to a minimum.

• Leave old barns for nesting or roosting owls to minimize habitat loss.

• Spread awareness to eradicate superstitions (owls represent death in some cultures) to prevent harm against owls.

• When bird watching, put the bird’s safety first — don’t jeopardize it for a better view or photograph.

WHAT IF I SEE AN INJURED OWL?

The first thing to do is call an owl rescue in your area. However, there are ways to help keep the owl comfortable while you wait for help to arrive. “A wild owl will instinctively fly away from humans so if you are able to pick it up, it is likely to be severely injured and will be further traumatized by being handled,” Paul and Nicola explain.

JOIN THE EFFORT

The organizations we spoke with are doing so much to help the owls. If you’re looking for a way to conserve these remarkable birds, it’s a good idea to take a leaf out of their book.

The Owl Research Institute, Liberty says, “is dedicated to long-term field research and population monitoring of many different owl species year-round.” They have live cams on the owls and nests, partnering with Explore.org so millions of viewers can watch owls raise their young. “It’s really magical. We’ve created citizen scientists programs where viewers help us collect behavioral information,” she says, adding that helping the owls can lead to better conservation efforts. To participate, she says, “There are compelling opportunities for citizen scientists to participate — the WAFLS surveys, Saw-whet migration banding nights, nest monitoring, box checking, and many others.”

Daniel tells us that the World Bird Sanctuary has bred and released over 1,000 barn owls back into the wild. “Additionally, we participate in studies to track the migration patterns of the small saw-whet owl, and we rehabilitate hundreds of owls annually that have been injured in one way or another,” he says, adding that you can get up close and personal with owls as a volunteer.

At the OWL (Orphaned Wildlife) Rehabilitation Society, they specialize in owl rehabilitation, rescue, and release. With over 700 to 800 birds in and out every year they could use your help too. The organization also focuses on awareness and education. And, as Rob explains, “We have an extensive foster parent program where we use our permanent birds to help raise young and hopefully return them to the wild.

The Owl Sanctuary, run by Paul Rose and Nicola Dawes, is also a rescue and rehabilitation centre. And, like most of these organizations, they care for owls and educate people about the conservation of wild and captive owls — all of which, they say, their lives are dedicated to doing.

OWLS AS PETS

Before you get excited — we’re not giving you tips about caring for a pet owl. In fact, we’re saying you shouldn’t have one at all! All the organizations we spoke with strongly oppose the idea, with good reason.

Even if your favorite book or movie makes owls as pets seem appealing, avoid this altogether. As Paul and Nicola explain, “Our intake of rescued/re-homed captive-bred owls has sadly increased since the Harry Potter books and movies.”

Daniel adds, “Owls, and all wild animals, make very bad pets. These are dangerous birds with very specific husbandry requirements.” And, as Liberty says, “It’s also illegal. The exception to this is licensed rescue/rehab groups who provide homes to owls who cannot be released back into the wild.”

Apart from the obvious drawbacks, it’s also terrible for the birds themselves. “They imprint on humans – meaning they kind of think they are a human, and then they cannot function properly in the wild anymore,” Liberty explains.

Instead of trying to domesticate a creature so obviously better-suited to the wild, volunteer to get cozy with owls without harming them.

FUN FACT: ORPHANED OWLS

Do you know enough about orphaned owls? “Many ‘orphaned’ owls are not usually orphaned at all, they may just be in the process of testing their wings. Here at the Sanctuary we call this the engine test!” Paul and Nicola explain. They tell us that fledglings spread out and away from their nests before they can fly. “It prevents overcrowding in the nest as the youngsters grow rapidly, and is nature’s way of minimizing any threat to the entire clutch from predators,” they add.

Unfortunately, young owls may lose their footing and fall to the ground. If you see one of these owls, contact an organization that can help. The best thing you can do, Paul and Nicola say, “is make sure it is out of the way of direct harm from predators, vehicles and people by putting it in the branches of the nearest tree, and quietly walking away.” Unless an owl is clearly injured, never take it out of its natural habitat.